“Thomas [Mann] paid his bill and walked towards his grandmother’s house. He could see his two sisters now, waiting for the rest of the story. Both of them in their night attire, and he could see Heinrich sitting apart from them and always in a story their mother would sigh and say that she had work to do and would continue the story tomorrow. And they would appeal to her, beg her to finish the story and she always would.

The young composer’s name was Johann Sebastian Bach, she said, and he walked to Lübeck through wind and rain and often he could find no boardinghouse and had to sleep in haystacks or in fields. Often, he was hungry. Very often he was cold. But he was always sure of his purpose. If he could get to Lübeck, he would meet the man who would help him to become a great composer.

Buxtehude was almost in despair. Some days he really believed that his sacred knowledge would be buried with him. On other days, in his heart, he knew that someone would come and he dreamed that he would recognize the man immediately and he would take him to church, and he would share his secrets with him.

‘How would he recognize the man?’ Carla asked. ‘The man would have a light in his eyes, or something special in his voice,’ her mother said.

‘How could he be sure?’ Heinrich asked.

‘Wait! He is still on the journey and worried,’ she went on.

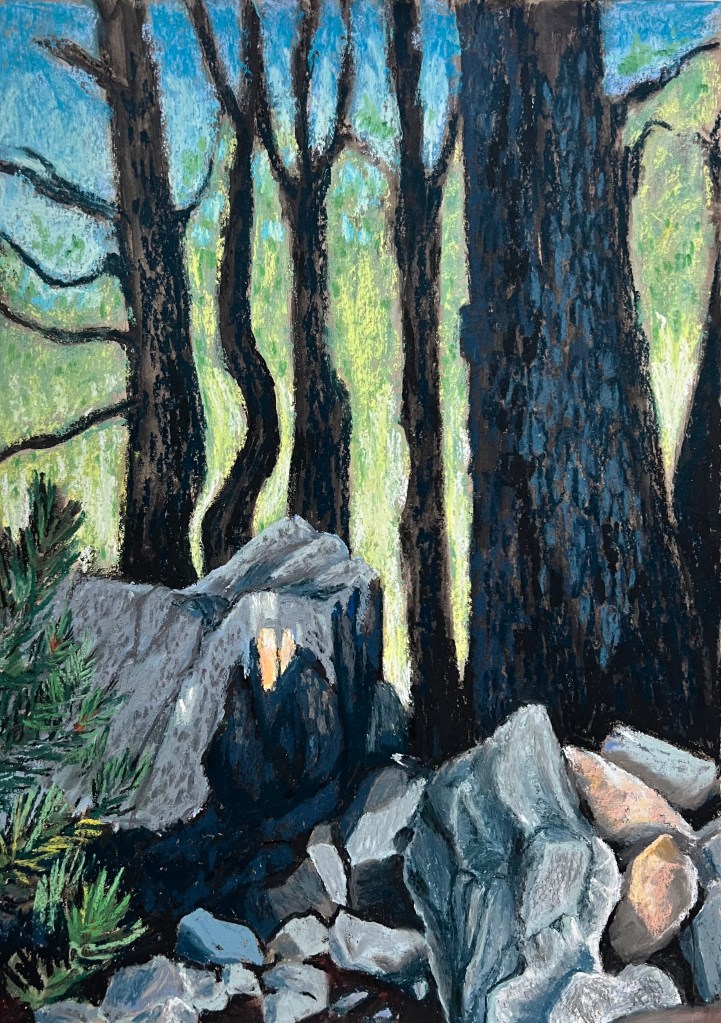

Every day the walk seems longer. He has told the man he works for that he will be away only a short time. He does not realize how far Lübeck is. But he does not turn back. He walks on and on, asking all the time how far Lübeck is. But it is so far that some people he meets have never even heard of Lübeck and they advise him to turn back. But he is determined not to, and eventually when he reaches Lüneberg, he is told that he is not far from Lübeck. And the fame of Buxtehude has spread to there. But because of all his time on the road, poor Bach, normally so handsome, looks like a tramp. He knows that Buxtehude will never receive a man as badly dressed as he is. But he is lucky. A woman in Lüneberg, when she learns of Bach’s plight, offers to lend him the clothes. She has seen the light in him.

And so Bach arrives in Lübeck. And when he asks for Buxtehude, he is told that he will be in the Marienkirche practicing the organ. And as soon as Bach steps into the church, Buxtehude senses that he is no longer alone. He stops playing and looks down from the gallery and sees Bach and behind him he sees the light, the light Bach has carried with him all the way, something glowing in his spirit. And he knows that this is the man to whom he can tell the secret.

‘But what is the secret?’ Thomas asked.

‘If I tell you, will you promise to go to bed’

‘Yes.’

‘It is called beauty,’ his Mother said. ‘The secret is called beauty. He told him not to be afraid to put beauty in his music. And then for weeks and weeks and weeks, Buxtehude showed him how to do just that.’

‘Did Bach ever give the woman back the clothes?’ Thomas asked.

‘Yes, he did on his way home. And on their piano, he played music for her that she thought came from heaven.’ “

Excerpt from Colm Toibin’s The Magician pgs. 496-497