Robin L. Chandler, 2026

“Wake up, wake up

Wake up, wake up

Wake up, wake up

Wake up, wake up

Time we were all gently rising up”

Lyrics excerpt from the Irish folk music duo Ye Vagabonds song Wake Up (listen here on youtube).

“Wake up, wake up

Wake up, wake up

Wake up, wake up

Wake up, wake up

Time we were all gently rising up”

Lyrics excerpt from the Irish folk music duo Ye Vagabonds song Wake Up (listen here on youtube).

The production of a work of art throws a light upon the mystery of humanity. A work of art is an abstract or epitome of the world. It is the result or expression of nature in miniature. For, although the works of nature are innumerable and all different, the result or the expression of them all is similar and single. Nature is a sea of forms radically alike and even unique. A leaf, a sunbeam, a landscape, the ocean, make an analogous impression on the mind. What is common to them all, — that perfectness and harmony, is beauty. The standard of beauty is the entire circuit of natural forms, — the totality of nature; which the Italians expressed by defining beauty “il piu nell’ uno.” Nothing is quite beautiful alone: nothing but is beautiful in the whole. A single object is only so far beautiful as it suggests this universal grace. The poet, the painter, the sculptor, the musician, the architect, seek each to concentrate this radiance of the world on one point, and each in his several work to satisfy the love of beauty which stimulates him to produce. Thus is Art, a nature passed through the alembic of man. Thus in art, does nature work through the will of man filled with the beauty of her first works.

Excerpt from Ralph Waldo Emerson’s essay Nature published in Ralph Waldo Emerson Collection: Collected Essays and Lectures (p.9) published in 1849.

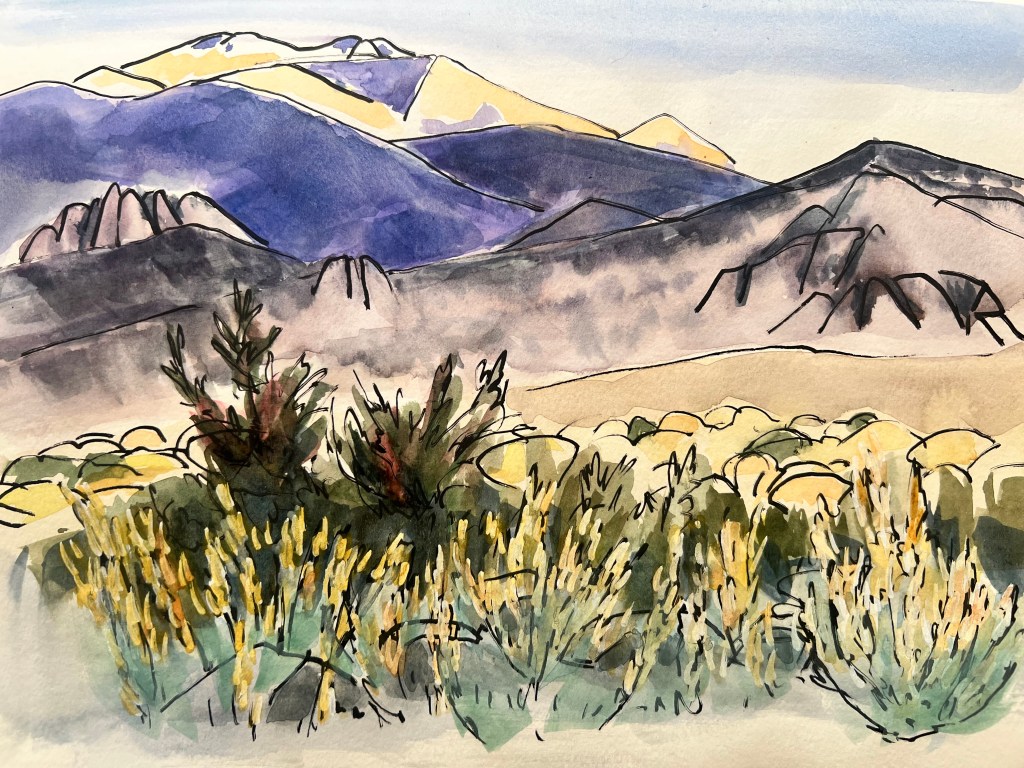

The Buttermilks Twilight. Robin L. Chandler, 2025

“Dürer was the first to take nature – a grassy meadow, for example, something completely mundane – and portray it. That kind of depiction hadn’t been done before. Until then, plants were always symbolic, like the lilies in a picture of the Virgin Mary. Earlier, each plant had a specific meaning. Dürer portrayed the meadow simply as a meadow – and that was completely revolutionary…..art doesn’t reside in nature as pure reality that you can depict directly. That doesn’t work anymore. Nature is no longer the innocent nature if once was…..

to make secretive is also to create a clearing in which something becomes visible, in which room for a new perception is created, but not in the scientific sense, in the mythological……

art brings all of the disparate kinds of knowledge into a new system. It brings this knowledge together and creates a unified view that must be constantly reinterpreted. It cannot be defined for all time…..

as a painter, one always hopes that under the surface, underneath what is visible, whether bricks or whatever, there’s something that will later mean more than what people see today. That is the veil…..that the painting already knows what will be in two centuries, what those looking at the painting will see in it in two hundred years. The veil of Isis can be a brick or a forest or whatever is painted and what is hidden beneath it is fed by the proceeding centuries but will also work in the centuries to come.”

Excerpt from Anselm Kiefer: In Conversation with Klaus Dermutz (New Delhi, India: Seagull Books, 2019) pps. 230 – 234

Twilight in a meadow in Bishop. Robin L. Chandler, 2025

“In 1750, nearly all of the world’s 750 million people, regardless of where they were or what political or economic system they had, lived and died within the biological old regime. The necessities of life – food, clothing, shelter, and fuel for heating and cooking – mostly came from the land, from what could be captured from annual energy flows from the sun to the Earth. Industries too, such as textiles, leather, and construction, depended on products from agriculture or the forest. Even iron and steel making in the biological old regime, for instance, relied upon charcoal made from wood. The biological old regime thus set limits not just on the size of the human population but on the productivity of the economy as well.

These limits would begin to be lifted over the century from 1750 to 1850, when some people increasingly used coal to produce heat and then captured that heat to fuel repetitive motion with steam-powered machines, doing work that previously had been done with muscle. The use of coal-fired steam to power machines was a major breakthrough, launching human society out of the biological old regime and into a new one no longer limited by annual solar energy flows. Coal is stored solar energy, laid down hundreds of millions of years ago. Its use in steam engines freed human society from the limits imposed by the biological old regime, enabling the productive powers and numbers of humans to grow exponentially. The replacement – with steam generated by burning coals – of wind, water, and animals for powering industrial machines constitutes the beginning of the Industrial Revolution and ranks with the much earlier agricultural revolution in importance for the course of history. The use of fossil fuels – first coal and then petroleum – not only transformed economies around the world but also added greenhouse gases to Earth’s atmosphere.”

Excerpt from Robert B. Marks’ The Origins of the Modern World: A Global and Environmental Narrative from the Fifteenth to the Twenty-First Century. Fifth Edition (p. 101 – 102)

The concept of the biological old regime, as discussed by Dr. Marks in great detail in Chapter One of the book, is based upon relationships, such as the rise of civilization and the agricultural revolution, the relationships between towns or cities and the countryside, between elites and peasants (also called agriculturalists or villagers), between civilizations and nomadic pastoralists, and between people and the environment

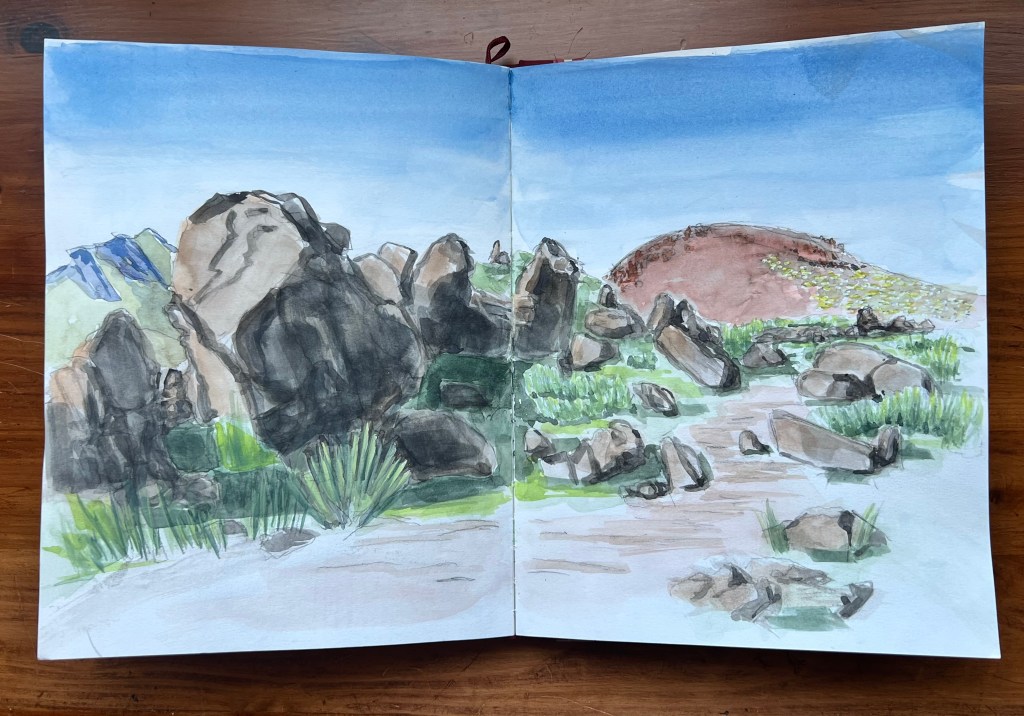

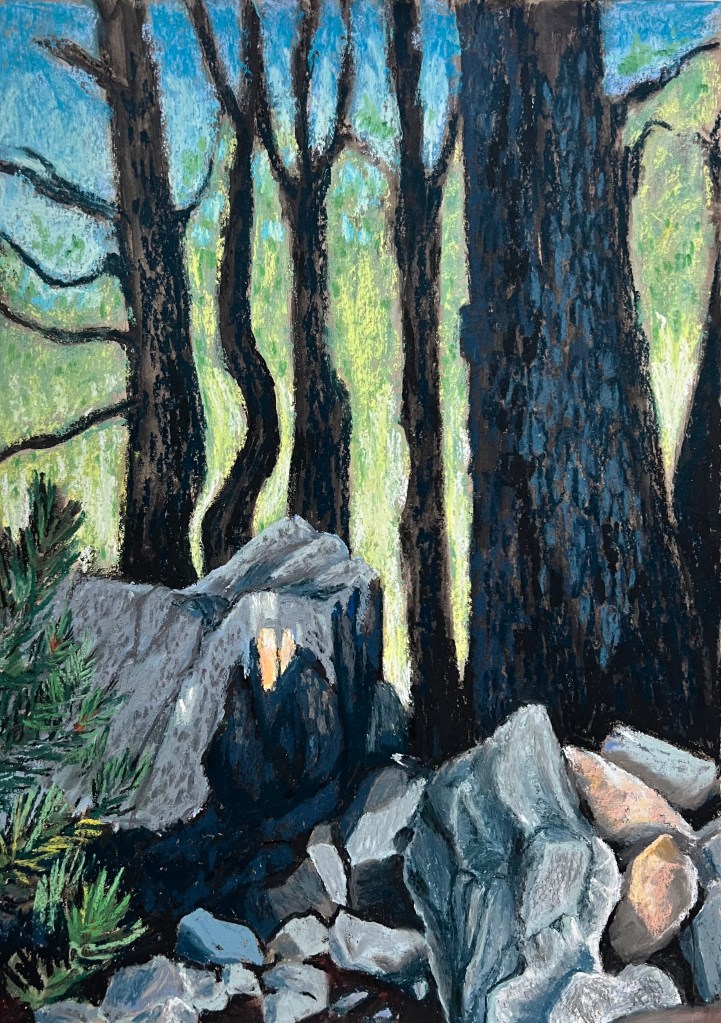

“…..on a September afternoon…..I return to the Buttermilks, walking about six miles roundtrip on the wash-boarded and rutted road up to the monster boulders known as Grandma and Grandpa Peabody, a favorite haunt of rock climbers. It is an amazing hike. I meet and talk with several people who call Payahuunadu their home. I am hooked on the Buttermilks! Storms linger in the valley and the day is a patchwork of blue skies, rainbows, and occasional downpours, but mostly a sensational cloud cover frames the mountain the Numu Paiute called Winuba (“Standing Tall”). Winuba is known to many as Mount Tom, and at 13,658 feet is the commanding peak of the Upper Owens Valley. I scramble amongst the granite boulders and marvel at their size. Grandpa Peabody is 50 feet high and 65 feet in diameter. Based on analysis of the boulders’ composition, geologists conclude that earthquakes shook these boulders loose from the ridgecrest and they rolled downslope, coming to rest in this field. I made this pastel in the studio from a photograph I took that day; the large pink boulder on the left is Grandpa Peabody.”

Excerpt from my book Awakened in the Range of Light: Art, Pilgrimage, and Friendship in the Sierra Nevada (p.42)

The Slim Princess is an oil fire 4-6-0 “Ten Wheeler” type narrow-gauge steam locomotive built in 1911 by the Baldwin Locomotive Works of Philadelphia, Pennsylvania. This incredible machine is preserved by the Eastern California Museum (in the Larry Peckham Engine House) and has been lovingly restored and maintained in operable condition by a devoted cadre of volunteers who I recently watched laboring on the engine. Working from a photograph I made onsite, I painted this pastel.

“…..the Slim Princess worked the Nevada California Oregon line for 15 years, eventually sold to the Southern Pacific narrow gauge line. Mining and timber and farming in east California, Nevada and points west kept railroad companies going since the 1880s. The Carson and Colorado Railroad Company was incorporated in 1880 running on the narrow-gauge lines.”

Excerpt from Sierra Wave Media, March 30, 2021

“…..a little more than ten years later the Southern Pacific took over the Carson and Colorado. The ever-present hope of a southern railroad was encouraged. Collis P. Huntington, head of the greater company, decided to complete the line through the valley, connecting the transcontinental systems to the south and the north. Before he proceeded with that plan, death claimed him, and his successors held a different view. When the Los Angeles aqueduct required large quantities of freight, the long-wanted [rail]road was built, and its last spike was driven at Owenyo October 18, 1910. It gave the valley a southern rail connection, though the narrow-gauge traversing Owens Valley as far as Owenyo has never been standardized…..the ‘Slim Princess,’ as the narrow-gauge was locally dubbed, would be made a part of a through north-and-south interior system. But those improvements have been completed, and there still remains 134 miles of the narrow-gauge which Mills said had been ‘built 300 miles too long and 300 years too soon.’ “

Excerpt from W.A. Chalfant’s The Story of Inyo (revised edition 1933), p. 313-314

“The reality bequeathed us by centuries of pioneering and its industrial sequel made our great need the creation of a new reality. But only spiritual force can create. Reason directs and conserves. Reason, it follows, was an ideal guide for the progress westward: and remains an ideal preservative for the traditional moods. Pragmatism, in its servility to Reason, is supine before the pioneer reality whose decadent child it is. As a recreative agent of American life – which it claimed to be – it was destined to be sterile: destined to rationalize and fix whatever world was already in existence. The legs of the pioneer had simply become the brains of the philosopher.” (28 – 29)

“America was builded on a dream of fair lands…..in the infinitely harder problems of social and psychic health, the dream persists. We believe in our Star. And we do not believe in our experience. America is filled with poverty, with social disease, with oppression and with physical degeneration. But we do not wish to believe that this is so. We bask in the benign delusion of our perfect freedom. In the same way, the pioneer…..believed only in pressing on. There is this great difference, however. Physical prowess throve best unconsciously and fostered by a dream. Spiritual growth without the facing of the world is an impossible conception.” (31 – 32)

Excerpts from Our America by Waldo Frank published in 1919

“Over that [1929] summer, [Georgia] O’Keefe worked her way through the standard paintings of santos, Ranchos de Taos church, and Taos Pueblo itself, but hints of her later work appeared as well. Particularly in a series of paintings of penitence crosses against a backdrop of a southwestern night sky, O’Keefe illustrated the spiritual inspiration she found in the New Mexico landscape. Perhaps the best-known painting from the summer, however, is The Lawrence Tree…..O’Keefe described the painting…..’I had one particular painting, that tree in Lawrence’s front yard as you see when you lie under it on the table with the stars it looks as tho it is standing on its head.’…..the work shows O’Keefe’s sensual appreciation of New Mexico as well as her engagement with [D. H.] Lawrence‘s writing. Lawrence had described the tree himself in St. Mawr, and Lawrence’s work remained in O’Keefe’s library throughout her life. Although Lawrence typically saw the tree with some ambivalence, O’Keefe made it entirely her own. In the painting, the tree reaches up and seems to kiss the sky, much as O’Keefe herself once said she wanted to do.” (177)

Excerpt from Flannery Burke‘s From Greenwich Village to Taos: Primitivism and Place at Mabel Dodge Luhan’s (Lawrence, Kansas: University of Kansas Press, 2008)

“The rivers of fluid fire that suddenly fell out of the sky and exploded on the earth near by, as if the whole earth had burst like a bomb, frightened her from the very core of her, and made her know secretly and with cynical certainty, that there was no merciful God in the heavens. A very tall, elegant pine-tree just above her cabin took the lightning, and stood tall and elegant as before, but with a white seam spiraling from its crest, all down its tall trunk, to earth. The perfect scar, white and long as lightning itself. And every time she looked at it, she said to herself, in spite of herself: There is no Almighty loving God. The God there is shaggy as the pine-trees, and horrible as the lightning. Outwardly, she never confessed this. Openly, she thought of her dear New England Church as usual. But in the violent undercurrent of her woman’s soul, after the storms, she would look at that living seamed tree, and the voice would say in her, almost savagely: What nonsense about Jesus and God of Love, in a place like this! This is more awful and more splendid. I like it better. The very chipmunks, in their jerky helter-skelter, the blue jays wrangling in the pine-tree in the dawn, the grey squirrel undulating to the tree-trunk, then pausing to chatter at her and scold her, with a show of fearlessness, as if she were the alien, the outsider, the creature that should not be permitted among the trees, all destroyed the illusion she cherished, of love, universal love. There was no love on this ranch. There was life, intense, bristling life, full of energy, but also, with an undertone of savage sordidness.” (167-168)

Excerpt D. H. Lawrence‘s St. Mawr (New York, New York: Penguin Books, 1997)

“In the beginning there were stories and the stories were made of Earth. Rocks and rivers, mountains and sea, these were the gods and the gods moved within them.” (p.225)

In 2013, the entirety of the novel Moby Dick was translated into emojis, those little ideograms of smiling faces and pets and objects that populate our phones and number around 1000…their appeal seems to be based on the strange and paradoxical combination of specificity and obscurity that they embody…they purport to transcend cultural difference and cut a line of sincerity and clarity straight to the nebulous heart of what we mean to say. Yet for all that, emojis, particularly in combination, open wormholes of ambiguity.” (p.228)

“Yet directness and certainty remain a dream despite our words, despite our codes, despite our cyphers. Who can state for sure the meaning of Moby Dick? ‘Of whales in paint; in teeth; in wood; in sheet-iron; in stone; in mountains; in stars’: Ishmael, its narrator, could find them everywhere. Yet the whale itself, the white whale, the named whale, is elusive. What did it mean to Ahab? Why the obsession, the desire, the pursuit? Everything can mean something else, if only we could agree what. Augustine wondered whether we could decide simply by pointing and naming. Remember that Moby Dick, whose title names its prey, itself begins with an act of naming: ‘Call me Ishmael.’ Yet in saying that, it is clear, too, that any name would have sufficed. The willow is also ‘sallow,’ is also ‘osier.’ In such simple acts lie a world of ambiguity, and a history concealed from the eyes of the everyday. Nothing is steady. Meaning sways like the hull of a ship. Ahab, with leg of wood, and scars on his body like the ‘seam sometimes made in the straight, lofty trunk of a great tree,’ hunts over ocean and sea in a vessel of timber from which a mast extends like a great oak into the sky above. Nailed to it is a gold doubloon and at its top a man sits, in the masthead, watching the horizon, searching.” (p.228-229)

Excerpts from Aengus Woods’ Of Trees in Paint; In Teeth; In Wood; In Sheet-Iron; In Stone; In Mountains; In Stars published in Katie Holten’s The Language of Trees: A Rewilding of Literature and Landscape

“…Beauty in the Song is clearly not the idealized, symmetrical, or abstract beauty of the Greeks, although occasional references to symmetry occur as in the images of twin gazelles and twin teeth (4:3, 4:5, 6:6, 7:4). The poet presents impressionistic images rather than a definitive likeness. Beauty in the song is visual, aromatic and tactile; it is textured and complex – a synesthetic experience. Beauty is a function of the abundance of the natural world. It is a function of aliveness. Beauty only becomes intelligible through the Song’s figurative language, which collapses the distance between the lovers and the land they inhabit. What beauty actually looks like in the Song is a luxurious land, alive with sheep grazing on hillsides, gazelles bounding through mountains, and trees laden with fruit.” (p.22)

An excerpt from Rabbi Ellen Bernstein’s Toward a Holy Ecology: Reading The Song of Songs in the Age of the Climate Crisis