“In 1750, nearly all of the world’s 750 million people, regardless of where they were or what political or economic system they had, lived and died within the biological old regime. The necessities of life – food, clothing, shelter, and fuel for heating and cooking – mostly came from the land, from what could be captured from annual energy flows from the sun to the Earth. Industries too, such as textiles, leather, and construction, depended on products from agriculture or the forest. Even iron and steel making in the biological old regime, for instance, relied upon charcoal made from wood. The biological old regime thus set limits not just on the size of the human population but on the productivity of the economy as well.

These limits would begin to be lifted over the century from 1750 to 1850, when some people increasingly used coal to produce heat and then captured that heat to fuel repetitive motion with steam-powered machines, doing work that previously had been done with muscle. The use of coal-fired steam to power machines was a major breakthrough, launching human society out of the biological old regime and into a new one no longer limited by annual solar energy flows. Coal is stored solar energy, laid down hundreds of millions of years ago. Its use in steam engines freed human society from the limits imposed by the biological old regime, enabling the productive powers and numbers of humans to grow exponentially. The replacement – with steam generated by burning coals – of wind, water, and animals for powering industrial machines constitutes the beginning of the Industrial Revolution and ranks with the much earlier agricultural revolution in importance for the course of history. The use of fossil fuels – first coal and then petroleum – not only transformed economies around the world but also added greenhouse gases to Earth’s atmosphere.”

Excerpt from Robert B. Marks’ The Origins of the Modern World: A Global and Environmental Narrative from the Fifteenth to the Twenty-First Century. Fifth Edition (p. 101 – 102)

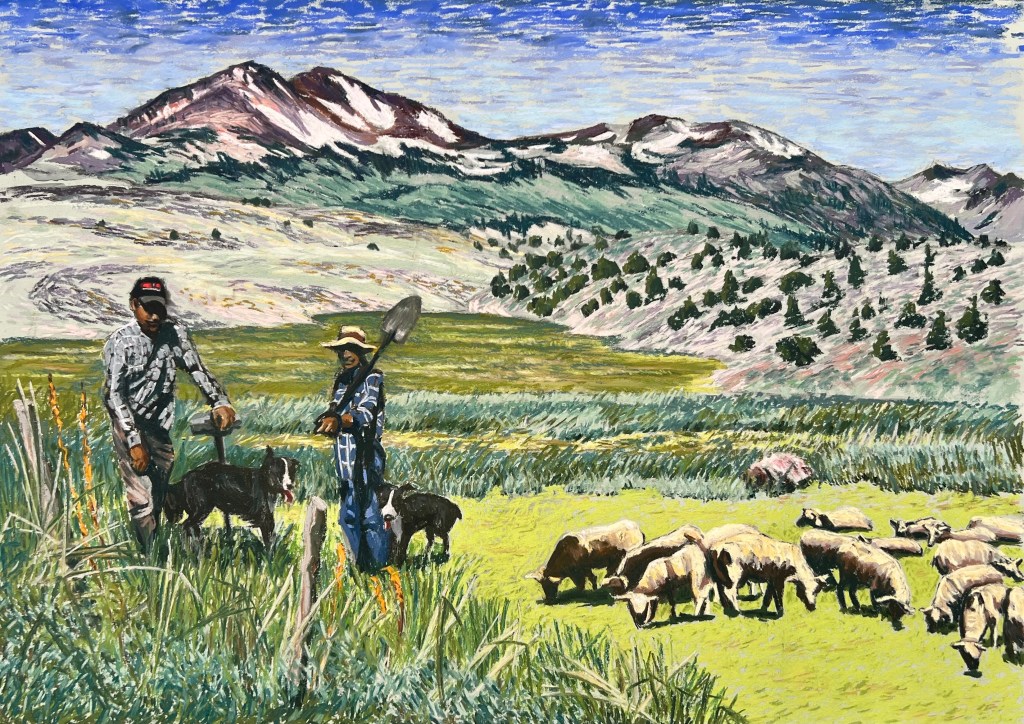

The concept of the biological old regime, as discussed by Dr. Marks in great detail in Chapter One of the book, is based upon relationships, such as the rise of civilization and the agricultural revolution, the relationships between towns or cities and the countryside, between elites and peasants (also called agriculturalists or villagers), between civilizations and nomadic pastoralists, and between people and the environment