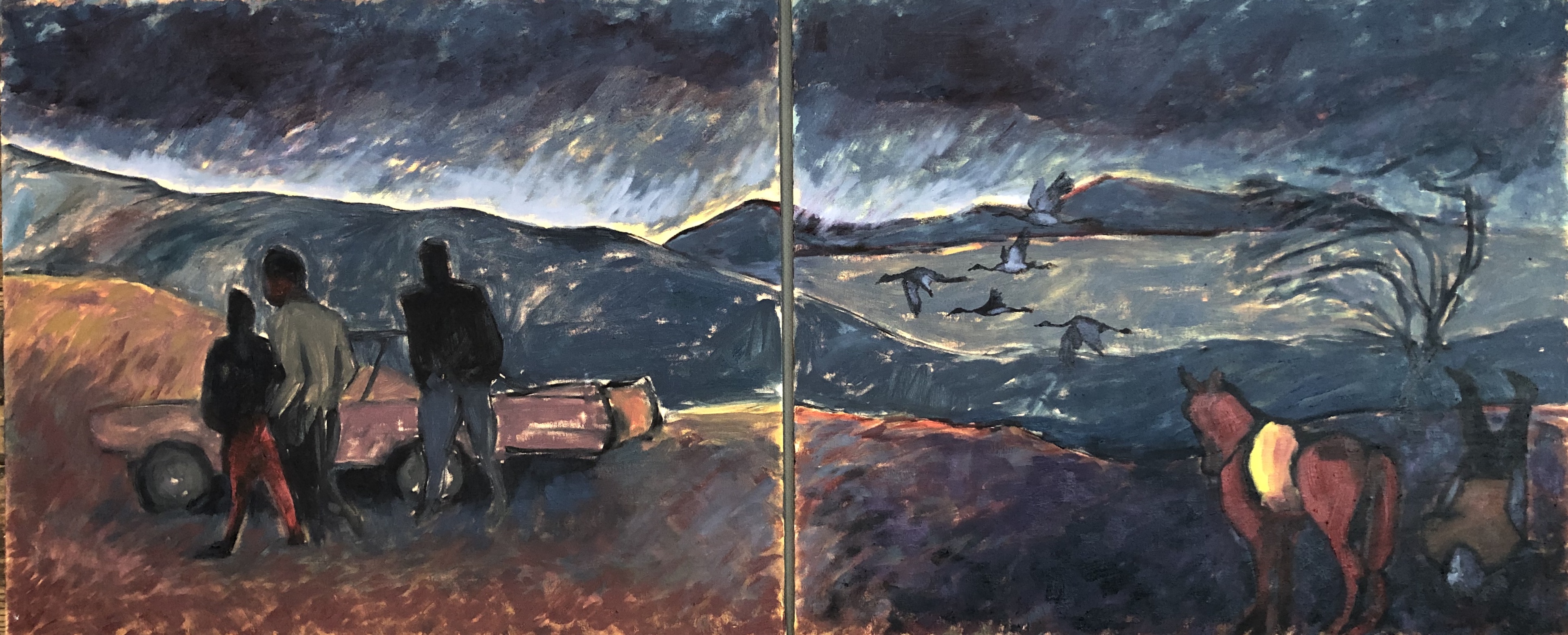

Robin L. Chandler, 2026

“Wake up, wake up

Wake up, wake up

Wake up, wake up

Wake up, wake up

Time we were all gently rising up”

Lyrics excerpt from the Irish folk music duo Ye Vagabonds song Wake Up (listen here on youtube).

“Wake up, wake up

Wake up, wake up

Wake up, wake up

Wake up, wake up

Time we were all gently rising up”

Lyrics excerpt from the Irish folk music duo Ye Vagabonds song Wake Up (listen here on youtube).

“So while this is a book about the music of memory, it also necessarily becomes a book about the memory of music and the deeper social memory of art – its ability to recall the catastrophes of war but also the optimistic promise and gleam of earlier eras, or what the critic Walter Benjamin called, with touching simplicity, “hope in the past.” This book in fact draws inspiration from Benjamin’s vision of the true purpose of history: to sort through the rubble of earlier eras in order to recover these buried shards of unrealized hope, to reclaim them, to redeem them. They are, as he saw it, nothing more or less than the moral and spiritual building blocks of an alternate future.”

Excerpt from Jeremy Eichler’s Times Echo: Music, Memory, and the Second World War (New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 2023) ebook p. 32

“Thomas [Mann] paid his bill and walked towards his grandmother’s house. He could see his two sisters now, waiting for the rest of the story. Both of them in their night attire, and he could see Heinrich sitting apart from them and always in a story their mother would sigh and say that she had work to do and would continue the story tomorrow. And they would appeal to her, beg her to finish the story and she always would.

The young composer’s name was Johann Sebastian Bach, she said, and he walked to Lübeck through wind and rain and often he could find no boardinghouse and had to sleep in haystacks or in fields. Often, he was hungry. Very often he was cold. But he was always sure of his purpose. If he could get to Lübeck, he would meet the man who would help him to become a great composer.

Buxtehude was almost in despair. Some days he really believed that his sacred knowledge would be buried with him. On other days, in his heart, he knew that someone would come and he dreamed that he would recognize the man immediately and he would take him to church, and he would share his secrets with him.

‘How would he recognize the man?’ Carla asked. ‘The man would have a light in his eyes, or something special in his voice,’ her mother said.

‘How could he be sure?’ Heinrich asked.

‘Wait! He is still on the journey and worried,’ she went on.

Every day the walk seems longer. He has told the man he works for that he will be away only a short time. He does not realize how far Lübeck is. But he does not turn back. He walks on and on, asking all the time how far Lübeck is. But it is so far that some people he meets have never even heard of Lübeck and they advise him to turn back. But he is determined not to, and eventually when he reaches Lüneberg, he is told that he is not far from Lübeck. And the fame of Buxtehude has spread to there. But because of all his time on the road, poor Bach, normally so handsome, looks like a tramp. He knows that Buxtehude will never receive a man as badly dressed as he is. But he is lucky. A woman in Lüneberg, when she learns of Bach’s plight, offers to lend him the clothes. She has seen the light in him.

And so Bach arrives in Lübeck. And when he asks for Buxtehude, he is told that he will be in the Marienkirche practicing the organ. And as soon as Bach steps into the church, Buxtehude senses that he is no longer alone. He stops playing and looks down from the gallery and sees Bach and behind him he sees the light, the light Bach has carried with him all the way, something glowing in his spirit. And he knows that this is the man to whom he can tell the secret.

‘But what is the secret?’ Thomas asked.

‘If I tell you, will you promise to go to bed’

‘Yes.’

‘It is called beauty,’ his Mother said. ‘The secret is called beauty. He told him not to be afraid to put beauty in his music. And then for weeks and weeks and weeks, Buxtehude showed him how to do just that.’

‘Did Bach ever give the woman back the clothes?’ Thomas asked.

‘Yes, he did on his way home. And on their piano, he played music for her that she thought came from heaven.’ “

Excerpt from Colm Toibin’s The Magician pgs. 496-497

Thelonious Monk and John Coltrane. Robin L. Chandler, 2021.

Many years ago, when we wanted to learn about jazz, our dear friend Peggy, a connoisseur of improvisational music, began our education with the 1961 album Thelonious Monk with John Coltrane. The album was recorded in 1957, when Monk and his quartet, featuring John Coltrane on tenor sax, were deep in their landmark six month residence at the Five Spot Café in New York’s East Village. To this day, over sixty years later, their grooves are rubies, my dear, gems I turn to when I need to bebop and blow the blues away.

The sun sets on the last July Saturday and I listen to a fado lament sung by Ercilia Costa and read Winter a poem by Czeslaw Milosz:

“And now I am ready to keep running

When the sun rises beyond the borderlands of death,

I already see mountain ridges in the heavenly forest

Where, beyond every essence, a new essence waits.”

The last few months, while we’ve all been sheltering-in-place, I have been teaching my grandniece and grandnephew some painting and music lessons. We live about 3,000 miles apart, so, these wonderful Sunday events are brought courtesy of phones, meeting software, and social media – anything that can help us keep a connection. Recently, we sang old folksongs together – some by Woody Guthrie and others traditional. The children are very young – for them they are sweet songs, they don’t yet know the stories behind them.

When I was their age I began to learn to play the guitar and sing. A few years later, when I was about eleven I discovered the great song collector and ethnomusicologist Alan Lomax. At my music teacher’s shop there was a big thick book of more than 600 pages that fascinated me. It was Lomax’s 1960 Folk Songs of North America: In the English Language that included the melodies and guitar chords transcribed by Peggy Seeger, sister of the beloved folk singer Pete Seeger. Somehow I scraped the money together, and about a year later, I bought this treasure chest representing all regions of the United States, song stories about sailors, farmers, pioneers, railroaders, hoboes, dam builders, cowboys, folks in good times and folks in bad times, and singing the stories taken from the countries of immigrants transplanted to this new country, many from the British Isles. The book includes a section called The Negro South where spirituals, work songs, ballads, and the blues are archived. In the 1960s it was a victory to say that African-Americans had a history, had a part in the American Story. A generation ago that was a step towards the light yet, as I opened the book to prepare for teaching my grand ones a few things about folk songs, the label used for the collection of African-American songs hit me hard. The framework is dated. It is a record documenting that era, but how do I tell little children about the pain and suffering that comes from the racism, which is the source of some of these songs? How do you tell that story? What do they need to know? As a historian and archivist, I understand and appreciate the book’s artifactual value, but from the perspective of an uninformed reader, without any context, I wonder. History is complex; when and how do you introduce the complexities? Some fifty years later, that book has traveled with me across the country and across my many paths. It’s been a constant in my life; and as I grew the music taught me empathy and I began to learn about the complexities. It opened the door to so much wonderful music – music I’ve played and sung, and music I’ve listened to and helped me become an archivist and historian. It put me on the path to discover the stories behind the songs. The book is a catalog of our roots, Americana, a music visited by many artists during the 1960s ranging from Peter, Paul, and Mary to Eric Clapton, the Rolling Stones to the Grateful Dead, and more recently by musicians such as Dave Alvin and Tony Dubovsky. That wonderful big black book and the stories it tells has played an important part in my life. And perhaps that is what I tell my grandniece and grandnephew; learn the truth about what was and with empathy be part of writing the new story and writing their new song.

Big Bill Broonzy (1903-1958) was an American blues singer, songwriter, and guitarist, who wrote and copyrighted more than 300 songs – some of his songs are included in the Folk Songs of North America. The Smithsonian Folkways Recordings also captured Mr. Broonzy singing both some of his songs and traditional songs like Trouble in Mind, C.C. Rider, and Midnight Special. On late nights, I love listening to Mr. Broonzy then turning around and trying to play his songs myself. I do OK on the singing, but he was a master guitarist, so I just try to get the rhythm guitar going. Born in Mississippi, he worked as a sharecropper, preacher, soldier in World War I, and later, after moving to Chicago as a Pullman Porter, a foundry worker. But through it all, there was always the music he wrote, played and recorded including folk songs, spirituals, country blues, urban blues, and some jazz. His voice is authentic, it is strong, it is ironic, it is sad, it is angry, it is wise, it is brilliant, and it is beautiful.

One of Mr. Broonzy’s most poignant blues compositions is the Black, Brown, and White Blues. It’s a song about the relentless Jim Crow…it always finds some place to roost. Mr. Broonzy “had written this protest song, which addressed the experiences of black war vets and the painful issue of preferential treatment by gradations of skin color, in 1945 and had offered it to RCA Victor, Columbia, Decca and several of the newly formed independent record companies, but none of them wanted to record it. As a result Mr. Broonzy had to wait until 1951 before he could record the song commercially in Europe for a white and overseas audience. In the US it took until after his death in 1958 to be released and was titled Get Back.” Relentless. I share the lyrics below. The Reverend Dr. Joseph Lowery giving the benediction paraphrased the song at the 2009 inauguration ceremony of President Barack Obama stating “we ask you to help us work for that day when black will not be asked to get back, when brown can stick around, when yellow will be mellow, when the red man can get ahead, man, and when white will embrace what is right.”

And here we are in May 2020, and once again we are a nation pushing the contours of its historic founding documents, hoping that those long cotton threads are strong and flexible. We are engaged in a mighty struggle. What vision of America will triumph: the fearful authoritarian contraction or the confident democratic expansion? Will our Bill of Rights be torn to pieces as we fight oppression with our questions, our demands, and our protest? Taking inspiration from Dr. Lowery, it is a good time to write and sing a new song about these struggles. The new song will be righteous, like Bill Broonzy’s, but it will sing a story about the struggle for justice and a vision of political power, economic opportunity, and respect for all.

**********

This little song I’m singing about,

People you know its true.

If you’re black and got to work for a living’ boy,

This is what they’ll say to you:

Chorus:

Now if you’re white, you’re all right,

And if you’re brown, stick a-round,

But as you’s black, O brother

Get back, get back, get back

I remember I was in a place one night,

Everybody was having fun,

They was drinkin’ beer and wine.

But me, they sell me none.

(Chorus)

I was in an employment office,

I got a number and got in line.

They called everybody’s number

But they never did call mine.

(Chorus)

Me and a man was workin’ side by side,

And this is what it meant.

They was payin’ him a dollar an hour

And they was payin’ me fifty-cent.

(Chorus)

I helped build this country,

I fought for it too.

Now, I guess you can see

What black man has to do

(Chorus)

I helped win sweet victory

With my plough and hoe.

Now I want you to tell me brother,

What you gonna do about the old Jim Crow?

Now if you’re white, you’re all right,

And if you’re brown, stick a-round,

But as you’s black, O brother

Get back, get back, get back

Taos, New Mexico is a beautiful place. Imagine a warm summer evening sitting by a creek that rolls quietly to the river Rio Grande; you feel the magic of water in the desert. Water grants life; renews life. So precious is a life. My mind’s eye travels miles in seconds. Looking down from the bridge that crosses the narrow Rio Grande gorge, I toss a pinyon branch and I watch it travel through the canyon by the pueblos on it’s journey to Santa Fe; and then at Albuquerque where the river flattens and widens and water birds play along the shore; and on past El Paso where the river becomes the border between Texas and Mexico – a shallow river – a place of crossings for wild things – those beings naturally wild, we call free and others made wild by violence and fear, tired, poor and hungry seeking relief and asylum. Precious lives. There is no need for brick and mortar; we have built a wall of fear.

Blessed am I able to freely sit and breathe and feel the special magic of a place. On this solstice day may the light shine and illuminate our way.

Happened upon the new Ry Cooder recording The Prodigal Son. It’s a good one. Keep thinking of the lyrics of his song Jesus and Woody inspired by Woody Guthrie’s song Jesus Christ where Woody (writing in 1940) speculates modern capitalist society would kill Jesus too. Listen to Woody sing here on YouTube. Ry’s lyrics – singing from Jesus’ perspective – stick with me:

“so sing me a song ‘bout this land is your land’

and fascists bound to lose

you were a dreamer, Mr. Guthrie, and I was a dreamer too…..”

“…..some say I was a friend to sinners

but by now you know it’s true

guess I like sinners better than fascists

and I guess that makes me a dreamer too…..”

Some memories are like small towns on country roads;

once well travelled, now enigmas signifying an interstate exit.

Sister reminded me Mom’s favorite perfume was Faberge’s Tigress.

Dad bought her Tigress every Christmas.

Tigress: the sleek bottle containing the amber liquid crowned with a tiger skin stopper.

Unconscious memories no longer a mystery.

“Comprehend without your head

and without your ears, listen

to noiseless, un-mouthed words.”[1]

My mother was a Tigress – that was no mask.

She comprehended the noiseless, un-mouthed words of others.

Listening without her head and ears she always saw the truth behind other’s masks.

No matter how deep it cut-to-the-bone she always spoke her truth.

See suffered no fools.

And she always gave herself away for the benefit of others.

Across time and space I see you.

I embrace you.

I love you Tigress for all you did and hoped for me.

Namaste.

Written while listening to Caetano Veloso singing Cucurrucucu Paloma en Vivo inspired by the lyrics translated from Portuguese to English.

[1]A quote from Attar’s poem The Conference of the Birds, translated by Shole Wolpe

bittersweet

hope tinged with sadness

lonely cup of coffee with Hopper’s Nighthawks

searching for something; wishing to share

rounded body of all things in one

painting

rough and smooth

wet and dry

loosing yourself in the the act, life emerges

rounded body of all things in one

“things that gave way entered unyielding masses,

heaviness fell into things that had no weight.”

From Ovid’s TheMetamorphoses, Book I, translated by Horace Gregory

Written listening to Thelonious Monk and Gerry Mulligan play Round Midnight on Mulligan Meets Monk recorded in New York City; August 12 – 13, 1957

Winter has brought short days, cold nights, and muted colors. But even in this grey rainy gloom, you can find light. Last weekend, I had the great pleasure of hearing the pianist Roger Woodward and members of the Alexander String Quartet play Dmitri Shostakovich‘s Piano Trio No. 2 in E Minor, Opus 67. It was January 20, 2018, the morning of the Women’s March marking a year since the Presidential inauguration. Shostakovich’s deeply moving music was inspired by the tragic discovery – as the Nazi armies retreated from their failed siege of Leningrad – of the Russian atrocities committed against Jewish People. I found the sobering music – particularly the strong chords of the opening of the third movement “Largo” appropriate for my reflections both political and personal. What was inconceivable has become all too real: capitalism flirts actively with fascism, and democracy is gravely challenged. Illness has struck my loved ones. Like standing in a field in winter, life seems almost absent. Time slips through your fingers; silence roars. Shostakovich’s music breaks your heart, but mends it just the same. Life continues, sleeping underground.